University of York: Law School

Innovation

Aerial View

The focus of the case study at the University of York is the new Law School, which will be part of the new Law and Management Schools building. The building is under construction at the time of writing, and will form a key aspect of the expansion of the university’s Heslington East campus. The development of this site, which is one of the biggest building projects in Yorkshire, will include a number of new academic buildings, student accommodation, sporting, and community facilities.

The new Law School is designed to support a problem-based approach to teaching and learning, which is student-centered, and where learning is driven by students working collaboratively on open-ended problems, and reflecting on their experience of dealing these problems.

A key element in the design of the space has been to provide students with an environment that encourages them to work across subject boundaries and to take responsibility for their own learning ‘the space will support the students in being responsible for their own research needs so that they can manage aspects of their own learning’ (Senior Academic).

On the ground floor of the new Law and Management Schools building will be the shared teaching spaces: lecture theatres, seminar and computer rooms, and a moot court for Law, with the offices for staff, researchers and administrative staff on the upper floors.

The first floor will house the problem based learning (PBL) zone for the Law School, which will consist of collaborative group study space, comfortable seating and desks, and flexible learning space. The law students will be divided into simulated law firms from the start of their degree, and throughout their course they will be presented with legally based problems to solve in collaboration with other students.

York Management School has a more traditional approach to teaching and learning, using lecture theatres and seminar rooms, and staff offices for small groups. An oval-shaped 200-seat lecture theatre has been created for innovative teaching ‘in-the-round’, which can be divided into two Harvard-style U-shaped spaces of different sizes.

Management School students are not expected to stay in and around the School when not being taught. The view taken by the Law School is that students are the ‘lifeblood’ of the School, and should use its facilities as much as possible to conduct group work and engage in informal social learning with fellow students and members of academic staff, and the PBL zone has been designed to facilitate this. Having worked together on the design and planning, the two Schools recognise that two very different approaches to teaching and learning are being supported in one building. ‘Law has a very different pedagogical approach than Management, so it does cause tensions’ ( Senior Academic). However, though the PBL zone is dedicated to Law undergraduates, the staff and postgraduates of the two Schools are content to be sharing research and social as well as teaching space.

Mission and Vision

Artists impression

The university is one of the leading institutions in the sector for teaching and research, and is advancing its position both nationally and globally. As part of the process of growth and development, from 2003 the Vice Chancellor led an exercise to create the longer term vision of the university, in consultation with departments, students and other stakeholders. Consequently, it was decided to increase student numbers from 10,000 to 15,000 through natural growth, create two new departments, expand the portfolio of courses, and support new directions in research. However, after 40 years of the university’s existence, the physical footprint of the campus was almost at capacity. Thus, to achieve the university’s vision for the future, it would require the development of a new campus. After considerable investigation, agreement was reached for development onto Heslington East.

Leadership and Governance

The university’s governing body is its Council. The executive is led by the Vice Chancellor and his senior management group of pro-vice chancellors and senior administrators. Aside from this is has a flat management structure, without faculties, and much of the decision making is taken at departmental level. Members of staff feel that this process is democratic, and that their voices are heard at all levels of the university administration: ‘If you are heard at the departmental level that is as good as being heard at the university level. You are never more than two steps from the Vice Chancellor’ (Academic). To support this democratic management structure, the corporate strategy of the university is designed to be empowering, by providing broad institutional aims, which are interpreted by the individual departments, providing them with considerable autonomy in academic business of teaching, learning, research, knowledge exchange and community activities.

The other side of the coin is that ‘…if you give departments a lot of power and responsibility then it is much more difficult to have coherence because departments go off and do their own thing’ (Senior Academic). Whilst this may present some difficulties in terms of having a central organizational direction, it does mean that teaching and learning are driven and developed by academics from within their own departments.

The university has just created a new 10-year University Plan after extensive consultation across the whole institution and with external stakeholders. Individual members and groups of staff are encouraged to engage with the development of the plan and have many opportunities to do so, For example, ‘each year we have an annual Head of Departments Away Day so academics are involved in the development of the corporate strategy and have the opportunities to present ideas that feed into it’ (Estates Manager). Supporting strategies for research, teaching and learning, business and community, estates and information, among others, are in process of redevelopment. Departments have two annual review meetings where their long-term and medium-term plans are refreshed in discussion with the Vice Chancellor, Pro-Vice Chancellors and the three Academic Co-ordinators, considering themes such as departmental strategy, student number growth and research targets.

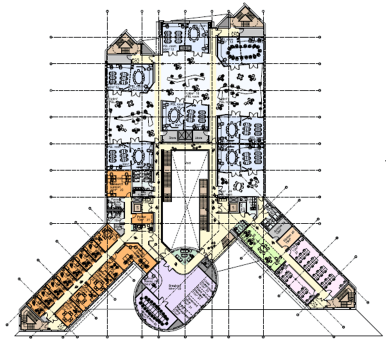

Floor Plan

The long-term and medium planning meetings provide greater cohesion between departmental strategies and the university’s corporate strategy, so that all of the planning is based on what the departments want to do and can achieve. In addition, the links between the departmental strategies and university corporate strategy are regularly revisited and academic plans are constantly being tested and reviewed.

The development of the new estates strategy is being led by the Pro-Vice Chancellor for Estates and Strategic Projects, who is engaging in structured dialogue with academics and support staff from all of the departments, schools and centres. Cross cutting themes such as the student experience, teaching and learning, and new ways of working are being handled through other interviews, surveys and focus groups. The annual departmental planning process also offers a formal opportunity for information about space needs to be fed to the PVC. Undoubtedly, this alignment of departmental planning with space needs and use is helped by the leadership of the PVC who acts as a conduit for academic input into the development of the physical campus. The PVC’s oversight of all strategic estates projects ensures that they are designed to address the needs of the client departments and the university as an academic institution, rather than being estates-led. The role was created to ensure that the needs of academics and students drive the design and management of space at the university and that both the estates strategy and the physical campus support the academic purpose of the university. This leadership has played a significant role in the development of innovative teaching and learning space, and was a crucial factor in the design of the new Law School.

Developing the Brief

One of the main drivers for the new Law School is the university’s vision to increase student numbers and its overall educational portfolio: ‘We started to think about whether we should have a Law School because it had emerged as an issue previously in the long term planning of the strategic direction of the university’ (Estates). But it was not simply an issue of student numbers, the university felt the fact that it did not offer a law degree was a significant shortcoming in its degree programme porfolio.

The development of the brief for the new Law School was academically driven and led by the Head of the new Law School. A key element of the development of the brief was that the university gave the Head of the Law school enough freedom to experiment and innovate, recognizing that such a project could only be driven by an academic with the experience and knowledge to carry it out.

This design of the Law School building was facilitated by a team of architects and project managers, who were were engaged to work on the development of the Heslington East campus. As part of the process, there was a working group, chaired by the PVC, which consisted of members of the two Schools, with estates and facilities management staff, the architects and project manager. The architects were involved in the process from the very beginning to help interpret the idea for the space and provide the working group with feedback to develop the brief. The architects’ role included settiing up activities that helped academics to envisage what the space would look and feel like, e.g., taping out spaces on the floor so that staff could get a real sense of the spatial options that might be available. This process was sometimes challenging as some academics found that ‘the scary element about being involved in the design process is that we are not building designers and we are not architects’ (Senior Academic).

While the idea for the Law School to adopt a problem based learning approach was driven by the Head of the Law School, this vision fitted well with the university’s mission to design its teaching and learning activities in ways that could be recognized as examples of York’s progressive approach to teaching and learning. The fact that the problem based model for teaching and learning matched the University’s sense of ambition helped to consolidate the support from other parts of the university: ‘if York was going to open a Law School it was going to be a Law School that was innovative and was not going to purely replicate what was going on elsewhere’ (Estates).

Furthermore, the willingness of the university to support a problem-based approach to teaching and learning in the Law School was seen as less of a risk by the fact that problem-based learning was already established in the Medical School at York.

There has been some attempt to get students involved in the development of the project. What is interesting about the approach that York has of engaging students in this process is that students are asked to come up with their own proposals, based on research and a sound business case.

Project Management

Artists impression2

In terms of project management, the university ensures that there is significant client involvement in its projects, with each project also having its project managers. This is done so that the projects can utilize the creativity of academics while not asking them to engage in work on which they have little experience. The university has its own strategic projects framework under which all strategic building projects are run. ‘We do not use a formal model of project management such as PRINCE2, but within our own framework we make sure we employ well qualified project managers with appropriate experience’ (Estates). Each project has a steering group, chaired by the Pro- Vice Chancellor for Estates and Strategic Projects, which has responsibility for defining the costed brief for the project, and ensuring that it is completed within budget, to time and to the required quality. The steering group comprises stakeholders from the academic and support staff and students as appropriate, A working group, usually chaired by a senior academic client, and supported by the project manager, does the detailed planning.

Research and Evaluation

The university has a formal post implementation review that is conducted usually one year after initial occupancy. This consists of asking the client groups to evaluate the project based on a series of questions, which include how well the brief reflected the needs of the project, the running of the proejct, how the building and space meet expectations, and how they rated the architect and contractors… The same questionnaire is administered to the estates department, facilities managers, commercial services and other relevant stakeholders and compared with the responses of the client group. The responses are coordinated by a strategic project manager and are reviewed by the University’s estates committee.

Under construction

As a result of this, there is clear evidence that the university is learning from previous projects and carrying these lessons forward to new developments: ‘There have been lessons learned from other projects like tightening up procedures, refining the strategic project framework, and the need to do more education with the client group about what construction projects involve. We also have to make sure that we have holistic budgets so that if there is an impact on the overall infrastructure it needs to be included in the budget’ (Estates).

There was an acknowledgement by some academics that the research and evaluation of new teaching and learning spaces should also consider the activities that have taken place in the new spaces: ‘in terms of evaluation of the space, we will have to include in those evaluations the suitability of the space for what we trying to achieve pedagogically…it seems to me to be ridiculous to measure it in any other way’ (Senior Academic). There is a strong feeling that students could be more involved in researching and evaluating these spaces: ‘it would be nice for the university to talk to students and to work more closely with students in terms of evaluating space’ (Student)

Recent Comments